A Naked Napoleon Flexes

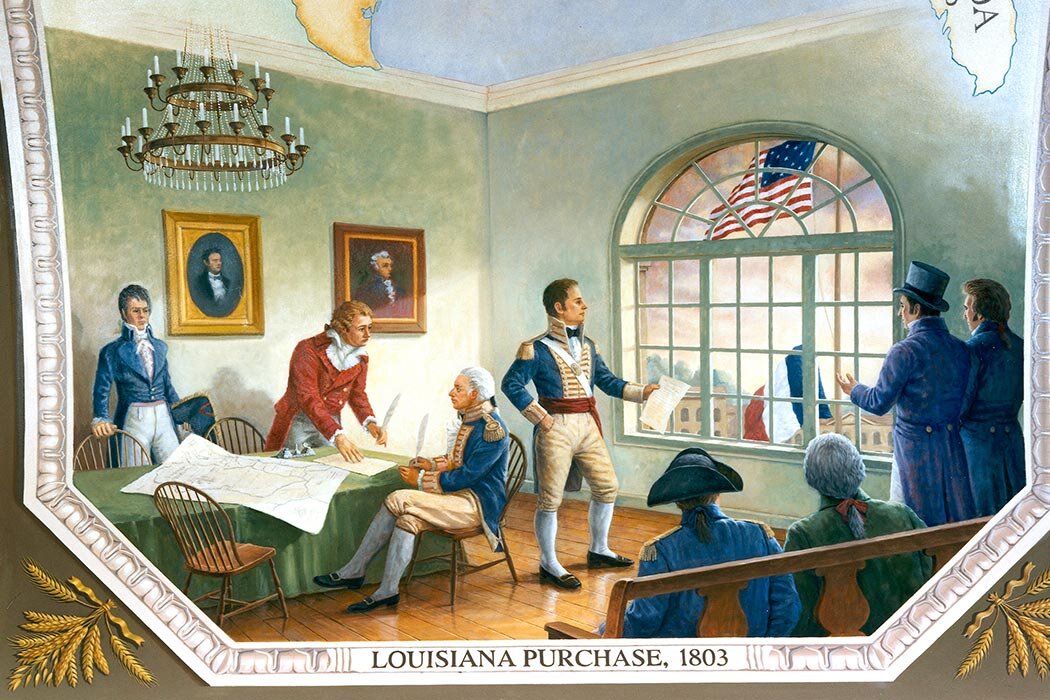

Napoleon Sells the Louisiana Territory

Britain and France happened to be in the midst of a negotiated two-year truce, but another war between the two was anticipated, if not scheduled. In Jefferson’s view, America’s strength depended on its patience to await that war.

The Smithsonian Magazine picks up the story: “The crunch came for Jefferson in October 1802. Spain’s King Charles IV finally got around to signing the royal decree officially transferring the territory to France. On October 16, the Spanish administrator in New Orleans arbitrarily ended the American right to deposit cargo in the city duty-free. This proclamation meant that American merchandise could no longer be stored in New Orleans warehouses. As a result, trappers’ pelts, agricultural produce and finished goods risked exposure and theft on open wharfs while awaiting shipment to the East Coast and beyond. The entire economy of America’s Western territories was in jeopardy.”

The article, written by Joseph Hariss, goes on to quote Jefferson: “There is, on the globe, one single spot,” Jefferson wrote, “the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market.” Jefferson’s concern was more than commercial. “He had a vision of America as an empire of liberty,” says Douglas Brinkley. “And he saw the Mississippi River not as the western edge of the country, but as the great spine that would hold the continent together.”

For Jefferson, this created one of the most significant crises since the American Revolution. He leaned on his ambassador in France, Robert Livingston to negotiate a stop to the treaty. Livingston, though a diplomatic neophyte, was an important, and largely unknown, figure in American history. He was one of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, and in his role as Chancellor of New York, administered the first oath of office to President George Washington. In this international role, the success or failure of American history would sit on his shoulders.

He was blown off again and again by his French counterparts and made little headway in stopping the transfer of the territory to Napoleon's control. Brittanica.com has this: “Livingston had but one trump to play, and he played it with a flourish. He made it known that a rapprochement with Great Britain might, after all, best serve the interests of his country, and at that particular moment an Anglo-American rapprochement was about the least of Napoleon’s desires.”

In need of more minds at the negotiating table, Jefferson sent James Monroe, his Secretary of State, to help Livingston in Paris. He was handed discretionary powers to spend $9M to secure New Orleans and parts of the Floridas. In financial straits at the time, Monroe sold his china and furniture to raise travel funds, asked a neighbor to manage his properties, and sailed for France in early 1803. Jefferson’s parting words were “The future destinies of this republic depended on your success.”

Napoleon was well into planning an invasion of Britain, and sent an expeditionary force of 40,000 to put down a revolution in Santo Domingo, led by Toussaint Louverture. Once that was quickly done, they would fortify a military presence in New Orleans, and set up France to be a colonial power in North America.

In American Creation, Ellis writes: the French Empire in North America would be a place where French debtors, criminals, and the derelicts could be shipped. Louisiana would become the granary or breadbasket for the highly lucrative French colonies in the Caribbean, chiefly Santo Domingo and Guadeloupe.”

Santo Domingo, with a population of more than 500,000, produced enough sugar, coffee, indigo, cotton and cocoa to fill 700 ships a year. As a result, Napoleon viewed it as France’s most important holding in the Western Hemisphere.

Ellis says: “Jefferson was prepared to run a high-stakes gamble, against the odds, that the French troops would get mired down in Santo Domingo and never make it to New Orleans. This proved to be an extraordinarily shrewd wager, but at the time it appeared to resemble a dangerous brand of wishful thinking.”

French General Leclerc, who led the expeditionary force, made a crucial mistake in his management of the Santo Domingo conflict. He initially befriended and supported Toussaint Louverture, then had him arrested and shipped off the island. Once the population saw enslavement was the French’s goal, all-out war ensued, and the French were doomed to lose, badly. With a population of 500,000, the French expeditionary force was outnumbered 10 to 1.

Ellis writes: “Leclerc could not believe it when hundreds of black prisoners strangled themselves to death rather than return to slavery. Women and children laughed at their executioners as they burned to death. Meanwhile, Leclerc’s army was virtually annihilated by a combination of reprisals, yellow fever, and malaria. In his last dispatch to Napoleon before his own death, Leclerc minced no words: “This colony is lost and you will never regain it. My letter will surprise you, but what general could calculate the mortality of four-fifths of his army.”

It was a catastrophe for the French army, which kept pouring troops into the breach and eventually suffered more than 60,000 casualties. For obvious reasons, no French expeditionary force ever made it to New Orleans. Jefferson’s gamble had paid off.

So it was a different situation when James Monroe arrived mid-year to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans. Napoleon recognized the annihilation of his expeditionary force had also annihilated his chance to establish a French empire in North America.

Author Joseph Ellis writes: “He told his foreign minister: ‘I renounce Louisiana. It is not only New Orleans that I will cede, it is the whole colony without reservation. I know the price of what I abandon. I renounce it with the greatest regret.’ When warned by his advisors that his decision was likely to establish the foundation for a rising American empire, Napoleon dismissed the warning as too farsighted: “In two or three centuries the Americans may be found too powerful for Europe, but my foresight does not embrace such remote fears.’”

Thierry Lentz, a historian and director of the Foundation Napoléon in Paris, contends that, for Napoléon, “It was basically just a big real estate deal. And he was in a hurry to get some money for the depleted French treasury. Napoleon managed to sell something that he didn’t really have any control over except on paper—there were few French settlers and no French administration over the territory.” As for Jefferson, notes historian Charles Cerami, “he actually wasn’t out to make this big a purchase. The whole thing came as a total surprise to him and his negotiating team in Paris, because it was, after all, Napoléon’s idea, not his.”

In the ultimate flex story, Napoleon was laying in his tub, sprinkled with cologne, when his two brothers came in and accused him of being impetuous. They promised to lead the opposition to him and the deal in French Parliament. Napoleon stood up naked in the tub and told them: “You will have no need to lead the opposition for I repeat there will be no debate. For the project has been conceived by me, negotiated by me, shall be ratified and executed by me, alone. Do you comprehend me?”He was blown off again and again by his French counterparts and made little headway in stopping the transfer of the territory to Napoleon's control. Brittanica.com has this: “Livingston had but one trump to play, and he played it with a flourish. He made it known that a rapprochement with Great Britain might, after all, best serve the interests of his country, and at that particular moment an Anglo-American rapprochement was about the least of Napoleon’s desires.”

In need of more minds at the negotiating table, Jefferson sent James Monroe, his Secretary of State, to help Livingston in Paris. He was handed discretionary powers to spend $9M to secure New Orleans and parts of the Floridas. In financial straits at the time, Monroe sold his china and furniture to raise travel funds, asked a neighbor to manage his properties, and sailed for France in early 1803. Jefferson’s parting words were “The future destinies of this republic depended on your success.”

Napoleon was well into planning an invasion of Britain, and sent an expeditionary force of 40,000 to put down a revolution in Santo Domingo, led by Toussaint Louverture. Once that was quickly done, they would fortify a military presence in New Orleans, and set up France to be a colonial power in North America.

In American Creation, Ellis writes: the French Empire in North America would be a place where French debtors, criminals, and the derelicts could be shipped. Louisiana would become the granary or breadbasket for the highly lucrative French colonies in the Caribbean, chiefly Santo Domingo and Guadeloupe.”

Santo Domingo, with a population of more than 500,000, produced enough sugar, coffee, indigo, cotton and cocoa to fill 700 ships a year. As a result, Napoleon viewed it as France’s most important holding in the Western Hemisphere.

Ellis says: “Jefferson was prepared to run a high-stakes gamble, against the odds, that the French troops would get mired down in Santo Domingo and never make it to New Orleans. This proved to be an extraordinarily shrewd wager, but at the time it appeared to resemble a dangerous brand of wishful thinking.”

French General Leclerc, who led the expeditionary force, made a crucial mistake in his management of the Santo Domingo conflict. He initially befriended and supported Toussaint Louverture, then had him arrested and shipped off the island. Once the population saw enslavement was the French’s goal, all-out war ensued, and the French were doomed to lose, badly. With a population of 500,000, the French expeditionary force was outnumbered 10 to 1.

Ellis writes: “Leclerc could not believe it when hundreds of black prisoners strangled themselves to death rather than return to slavery. Women and children laughed at their executioners as they burned to death. Meanwhile, Leclerc’s army was virtually annihilated by a combination of reprisals, yellow fever, and malaria. In his last dispatch to Napoleon before his own death, Leclerc minced no words: “This colony is lost and you will never regain it. My letter will surprise you, but what general could calculate the mortality of four-fifths of his army.”

It was a catastrophe for the French army, which kept pouring troops into the breach and eventually suffered more than 60,000 casualties. For obvious reasons, no French expeditionary force ever made it to New Orleans. Jefferson’s gamble had paid off.

So it was a different situation when James Monroe arrived mid-year to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans. Napoleon recognized the annihilation of his expeditionary force had also annihilated his chance to establish a French empire in North America.

Author Joseph Ellis writes: “He told his foreign minister: ‘I renounce Louisiana. It is not only New Orleans that I will cede, it is the whole colony without reservation. I know the price of what I abandon. I renounce it with the greatest regret.’ When warned by his advisors that his decision was likely to establish the foundation for a rising American empire, Napoleon dismissed the warning as too farsighted: “In two or three centuries the Americans may be found too powerful for Europe, but my foresight does not embrace such remote fears.’”

Thierry Lentz, a historian and director of the Foundation Napoléon in Paris, contends that, for Napoléon, “It was basically just a big real estate deal. And he was in a hurry to get some money for the depleted French treasury. Napoleon managed to sell something that he didn’t really have any control over except on paper—there were few French settlers and no French administration over the territory.” As for Jefferson, notes historian Charles Cerami, “he actually wasn’t out to make this big a purchase. The whole thing came as a total surprise to him and his negotiating team in Paris, because it was, after all, Napoléon’s idea, not his.”

In the ultimate flex story, Napoleon was laying in his tub, sprinkled with cologne, when his two brothers came in and accused him of being impetuous. They promised to lead the opposition to him and the deal in French Parliament. Napoleon stood up naked in the tub and told them: “You will have no need to lead the opposition for I repeat there will be no debate. For the project has been conceived by me, negotiated by me, shall be ratified and executed by me, alone. Do you comprehend me?”